A New York Times

bestseller, The Smartest Kids was selected by The Economist, The

Washington Post, The New York Times and Amazon.com as one of the

most notable books of 2013.

In a handful of nations, virtually all children are learning to make complex arguments and solve problems they’ve never seen before. They are learning to think, in other words. What is it like to be a child in these new education superpowers?

In a global quest to find answers for our own children, author and Time journalist Amanda Ripley follows three Americans embedded in these countries for one year. Kim, 15, raises $10,000 so she can move from Oklahoma to Finland; Eric, 18, exchanges an upscale Minnesota suburb for a booming South Korean city; and Tom, 17, leaves a historic Pennsylvania village for a gritty city in Poland.

Their stories, along with groundbreaking research into what works worldwide, reveal a pattern of startling transformation: none of these places had many “smart” kids a few decades ago.

They had changed. Teaching had become more serious; parents had focused on what mattered; and children had bought into the promise of education. A reporting tour de force, The Smartest Kids is a book about building resilience in a new world—as told by the young Americans with the most at stake.

With many thanks to Amanda Ripley

More here:

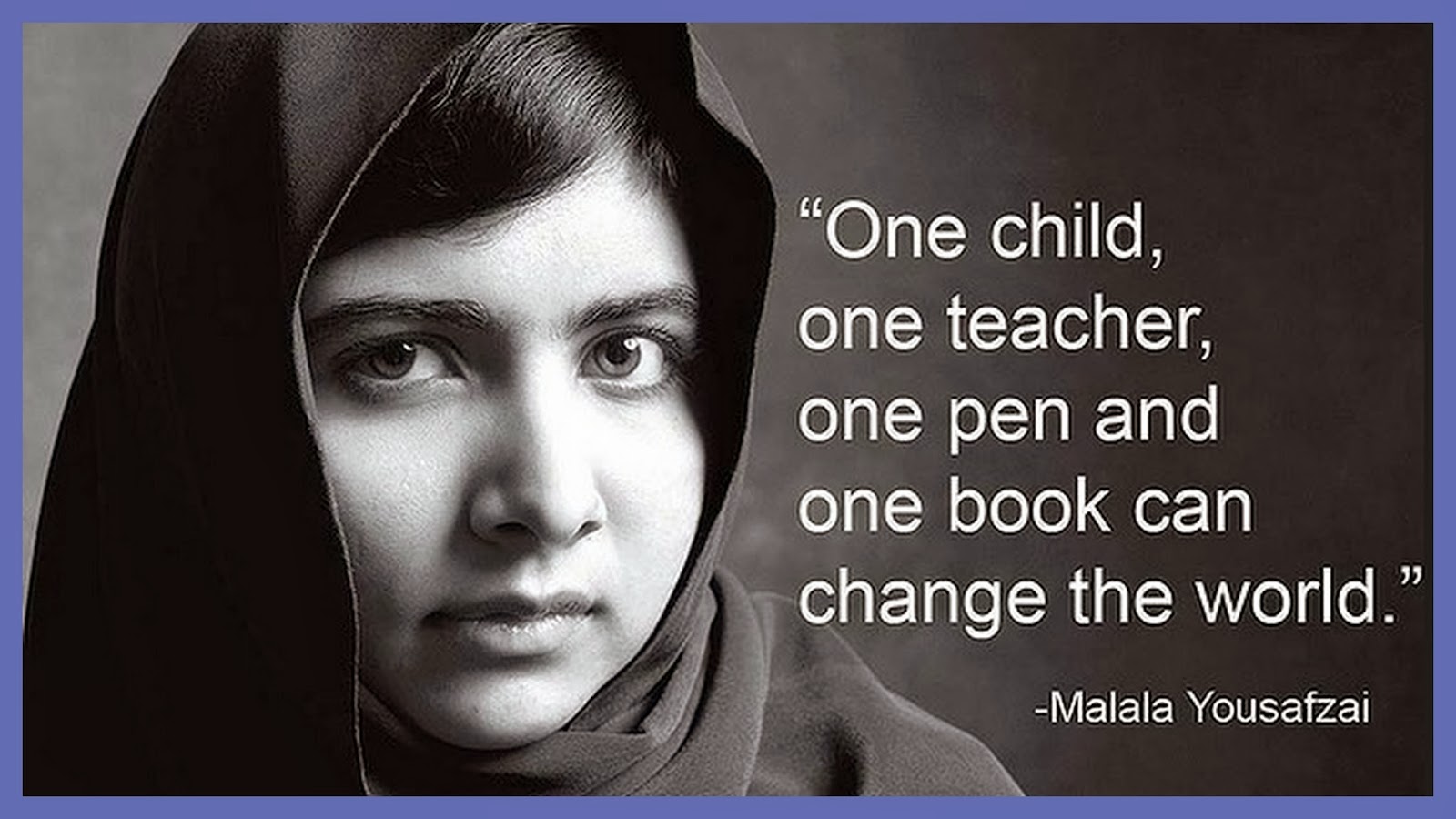

And words from a much younger voice say the same: Malala Yousafzai - see side bar.

In a handful of nations, virtually all children are learning to make complex arguments and solve problems they’ve never seen before. They are learning to think, in other words. What is it like to be a child in these new education superpowers?

In a global quest to find answers for our own children, author and Time journalist Amanda Ripley follows three Americans embedded in these countries for one year. Kim, 15, raises $10,000 so she can move from Oklahoma to Finland; Eric, 18, exchanges an upscale Minnesota suburb for a booming South Korean city; and Tom, 17, leaves a historic Pennsylvania village for a gritty city in Poland.

Their stories, along with groundbreaking research into what works worldwide, reveal a pattern of startling transformation: none of these places had many “smart” kids a few decades ago.

They had changed. Teaching had become more serious; parents had focused on what mattered; and children had bought into the promise of education. A reporting tour de force, The Smartest Kids is a book about building resilience in a new world—as told by the young Americans with the most at stake.

With many thanks to Amanda Ripley

More here:

Book Review here

By Jonah Edelman

The Smartest Kids in the World: And How They Got That Way is a gripping new book by Amanda Ripley that answers the

question, "what exactly is happening in classrooms in the countries that

out-perform the U.S. academically?" Ripley investigates this question by

spending time where the action is: in classrooms abroad, specifically in Poland,

South Korea, and Finland. Her "informants" are American high school students who

chose to study in those countries, and foreign students who come to the U.S. to

study.

I literally couldn't put The Smartest Kids in the World down. Ripley's characters are fascinating, her writing style is accessible, and her observations are fresh. There's no hint of tired education talking points or polarizing rhetoric. Ripley lets facts and firsthand observations guide her conclusions, not the other way around.

The first "aha" moment in The Smartest Kids is this: The performance of students in other countries has changed dramatically over time. In some countries, such as Poland and Finland, it has improved markedly; in others, such as Norway, which has a homogeneous population, low poverty rate, and generous social safety net, it has gotten significantly worse . The U.S. is actually the exception, not the norm, in that we have plodded along at the same level for decades as other countries pass us by.

The fact that student achievement levels across the world are so dynamic is an enormously hopeful fact. If other countries have steadily improved their performance, we can, too.

But how? What gives in the countries that have already surpassed the U.S. or are heading that direction? If you ask Ripley's "moles," the students from the U.S. who studied abroad in other countries, they'll tell you it's due to a few key things (and it's worth noting that their findings are backed up by a broad survey of students who have studied in and outside the U.S.).

The first is rigor. The level of expectations and work required in the non-U.S. classrooms is higher. The experience of Tom, a Pennsylvanian studying in Poland whom Ripley profiled, is a good example. In Tom's U.S. math classes, everyone used calculators. In Tom's classroom in Poland, everyone did math in their head, to the point that it seems like they were fluent in a language he was not. And after every test the teachers publicly announced how each student had performed, from a 1 (lowest) to a 5 (highest). Tom waited all year for someone to get a 5. No one ever did. Compare this to American classrooms, where A's are common and GPAs are often over a 4.0.

The second thing is the teachers. The teachers in the highest-performing countries come from the top of their college classes, even top-performers in college work extremely hard to get accepted into teacher-training schools, and teachers are highly respected and well-paid. You may already have heard that about Finland, for example, but Ripley uncovers something that isn't talked about much: it wasn't always that way.

In the 1970s the teacher training landscape in Finland looked a lot like it does now in the U.S.: a lot of teacher preparation programs, many of which were mediocre, a low bar for who was accepted into the programs, and limited oversight. As part of a broader education reform movement, the government closed low-performing teacher-training colleges and ensured the remaining schools raised the bar for entry. It was extremely controversial at the time. And it worked.

The last thing is parent involvement. In other countries, Ripley reports, parents aren't asked to come into the classroom and volunteer, or to fundraise for their school. Schools don't lament that lack of parent involvement because there is general agreement that parents should be involved where they are needed: at home. This is something that our family engagement program Stand University for Parents teaches our parents: the most impactful thing you can do for your child is to work with him or her on reading, writing, and math at home. (You can read more on my thoughts on the highest-impact family engagement here).

If you're interested in how to improve public schools, read Ripley's book today.

And after you read it, tweet about it to me @JonahEdelman. I'd love to hear your thoughts.

With thanks to The Huffington Post

I literally couldn't put The Smartest Kids in the World down. Ripley's characters are fascinating, her writing style is accessible, and her observations are fresh. There's no hint of tired education talking points or polarizing rhetoric. Ripley lets facts and firsthand observations guide her conclusions, not the other way around.

The first "aha" moment in The Smartest Kids is this: The performance of students in other countries has changed dramatically over time. In some countries, such as Poland and Finland, it has improved markedly; in others, such as Norway, which has a homogeneous population, low poverty rate, and generous social safety net, it has gotten significantly worse . The U.S. is actually the exception, not the norm, in that we have plodded along at the same level for decades as other countries pass us by.

The fact that student achievement levels across the world are so dynamic is an enormously hopeful fact. If other countries have steadily improved their performance, we can, too.

But how? What gives in the countries that have already surpassed the U.S. or are heading that direction? If you ask Ripley's "moles," the students from the U.S. who studied abroad in other countries, they'll tell you it's due to a few key things (and it's worth noting that their findings are backed up by a broad survey of students who have studied in and outside the U.S.).

The first is rigor. The level of expectations and work required in the non-U.S. classrooms is higher. The experience of Tom, a Pennsylvanian studying in Poland whom Ripley profiled, is a good example. In Tom's U.S. math classes, everyone used calculators. In Tom's classroom in Poland, everyone did math in their head, to the point that it seems like they were fluent in a language he was not. And after every test the teachers publicly announced how each student had performed, from a 1 (lowest) to a 5 (highest). Tom waited all year for someone to get a 5. No one ever did. Compare this to American classrooms, where A's are common and GPAs are often over a 4.0.

The second thing is the teachers. The teachers in the highest-performing countries come from the top of their college classes, even top-performers in college work extremely hard to get accepted into teacher-training schools, and teachers are highly respected and well-paid. You may already have heard that about Finland, for example, but Ripley uncovers something that isn't talked about much: it wasn't always that way.

In the 1970s the teacher training landscape in Finland looked a lot like it does now in the U.S.: a lot of teacher preparation programs, many of which were mediocre, a low bar for who was accepted into the programs, and limited oversight. As part of a broader education reform movement, the government closed low-performing teacher-training colleges and ensured the remaining schools raised the bar for entry. It was extremely controversial at the time. And it worked.

The last thing is parent involvement. In other countries, Ripley reports, parents aren't asked to come into the classroom and volunteer, or to fundraise for their school. Schools don't lament that lack of parent involvement because there is general agreement that parents should be involved where they are needed: at home. This is something that our family engagement program Stand University for Parents teaches our parents: the most impactful thing you can do for your child is to work with him or her on reading, writing, and math at home. (You can read more on my thoughts on the highest-impact family engagement here).

If you're interested in how to improve public schools, read Ripley's book today.

And after you read it, tweet about it to me @JonahEdelman. I'd love to hear your thoughts.

With thanks to The Huffington Post

And words from a much younger voice say the same: Malala Yousafzai - see side bar.