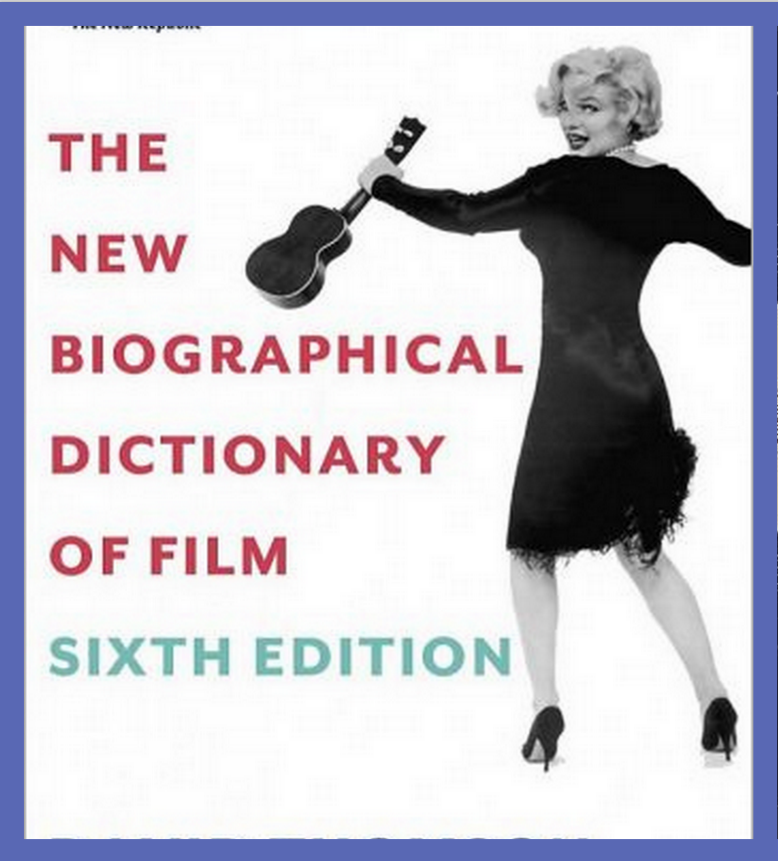

This month (actually May), sees the release of the sixth edition of David Thomson’s New Biographical Dictionary of Film, published for the first time in 1975. The book—now 1,154 pages long, with over 1,400 entries, more than 100 of them new to this edition—stands as a monument of film criticism, but a strange sort of monument, as if one had passed through the columns of a respectable-looking neoclassical temple to find the secret entrance to a tangle of graffiti-covered tunnels.

The most idiosyncratic and deeply personal of a filmgoer’s journals masquerading as a reference work, Thomson’s “dictionary” has enjoyed a nearly four-decade-long cult following (and provoked heated brawls among cinephiles, some of them in the pages of this magazine) precisely because of its author’s passionately subjective voice and stubbornly non-canonical choice of material. In 2010, it was ranked the No. 1 best film book ever written by a Sight and Sound critics’ poll.

I know some people—including

some of my most discerning cinephilic friends—find this book

off-puttingly opinionated and self-important, a gaudy shrine to its

author’s mercurial taste. They also contend that it’s lazily and

inconsistently updated, with multiple editorial and factual errors—a point I freely concede.

All I know is that in the 20 or so years I’ve had some edition or other of the New Biographical Dictionary on my shelf, I have yet to open it without reading at least three more entries than the one I was looking up. It’s a reference book into which I can pleasurably disappear into at any moment, and that’s not nothing, in this world.

All I know is that in the 20 or so years I’ve had some edition or other of the New Biographical Dictionary on my shelf, I have yet to open it without reading at least three more entries than the one I was looking up. It’s a reference book into which I can pleasurably disappear into at any moment, and that’s not nothing, in this world.

From Abbott and Costello to Terry Zwigoff, these mini-bios cover

whichever figures in film history Thomson bloody well feels like talking

about, for as long he feels like talking about them. Waiting to see

who’ll be included in each new update, based on Thomson’s seemingly

mercurial criteria, provides the slow-burn suspense of being a follower

of the New Biographical Dictionary. One of the main innovations of this sixth edition is the inclusion of several figures better known for their work in television than in movies,

two mediums whose increasing convergence Thomson readily recognizes. An

admiring entry on Bryan Cranston ends with this brief disquisition on

the future of cinema: “It’s hard to believe that the movies today would

have the courage and the persistence to do someone like Walter White.

Long-form television is the narrative form that has transcended movies

in the way, once, the novel surpassed cave paintings.”

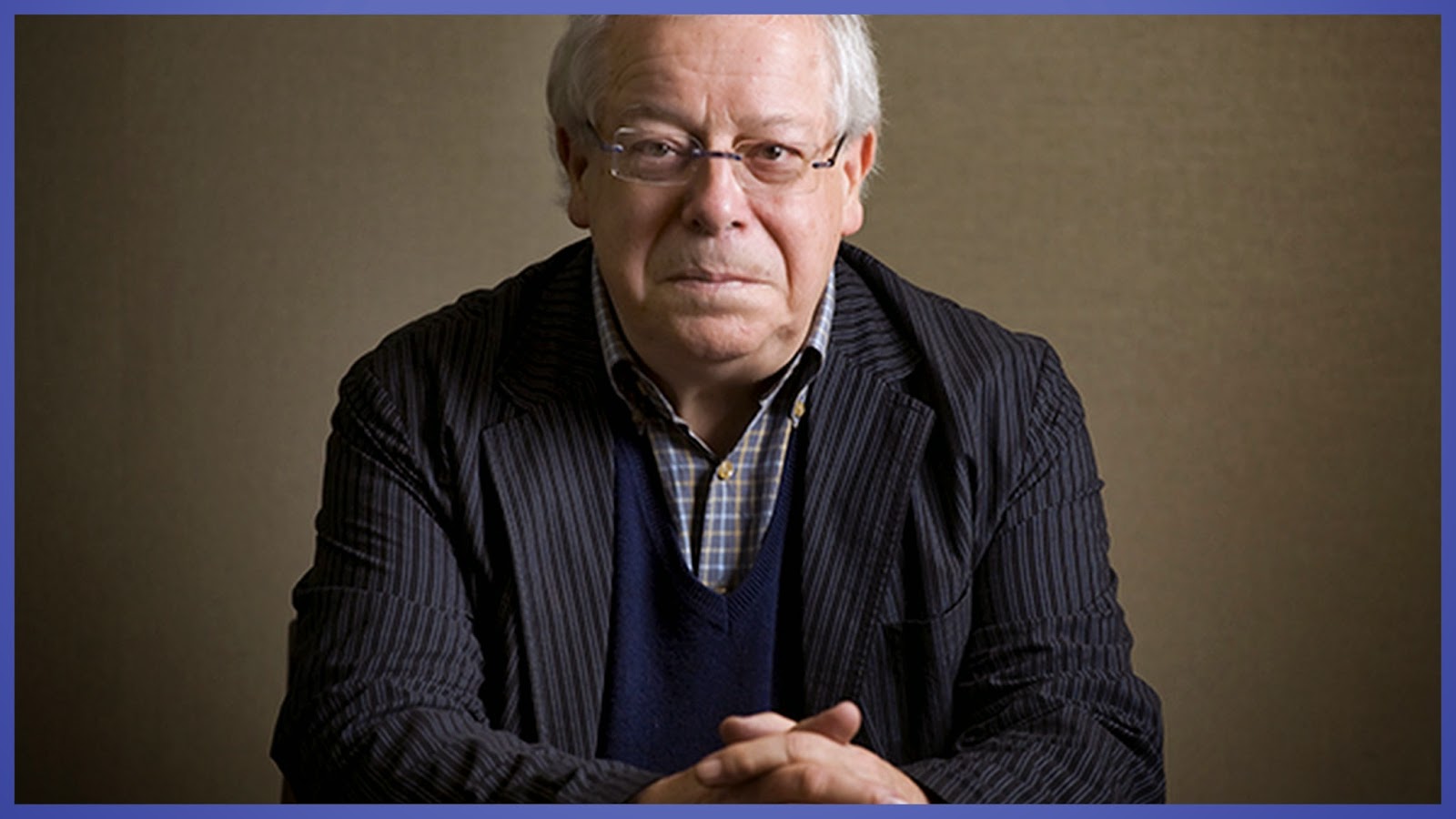

A British-born critic and film historian who lives in San Francisco and writes primarily for the New Republic,

Thomson, now in his early 70s, can be dismissive, peevish, and prickly.

He can sound obnoxiously fusty and sometimes flat-out sexist when

writing about women—when tracking the careers of contemporary actresses,

he has an annoying tendency to check in on the status of their sexual

appeal. (To be fair, Thomson can be nearly as judgey when it comes to

the physiques of aging actors: pity the Robert Redford of 1993’s Indecent Proposal,

about which Thomson writes that “the script was so undeveloped, and the

sex so absent, we were left with time to see how far Redford resembled

used wrapping paper.”)

And he can be breathtakingly catty, while pulling that Dorothy Parker trick of simultaneously being dead-on right: Anne Hathaway’s Les Miserables performance is “a shameless play on the equation between our tears, her Oscar, and makeup no cat would drag in.”

But the felicities of this half-dictionary, half-diary are to be

found in Thomson’s careening, confiding prose and the minute precision

of his observational eye, particularly when gazing upon something he

loves. Like, for example, the 19-year-old Lauren Bacall in her debut

role in To Have and Have Not, “watching everyone as if she had been up all night writing the script.” Or Bruce Dern’s eyes in Coming Home,

“lime pits of paranoia and resentment.” On old Hollywood, especially,

Thomson’s erudition and intimate attachment to his subject shine

through. And he can be breathtakingly catty, while pulling that Dorothy Parker trick of simultaneously being dead-on right: Anne Hathaway’s Les Miserables performance is “a shameless play on the equation between our tears, her Oscar, and makeup no cat would drag in.”

Nearly the entire entry on Eleanor Powell consists of a

description of how, locked in solitary confinement for the rest of his

life and allowed just one movie scene, Thomson would choose to watch

Eleanor Powell and Fred Astaire tap dancing to Cole Porter’s “Begin the

Beguine” in Broadway Melody of 1940.

It’s a free-associational reverie that ends on the startlingly abstract

image of “Powell’s alive frock” swishing around her legs for an extra

half-turn after the dance is over, “like a spirit embracing the person.”

The New Biographical Dictionary contains a seeming

infinitude of moments like that—poetic digressions that leave you

wondering (or, if you’re a hater, shaking your head) at the unlikely

publishing miracle by which one person’s private jottings somehow

Trojan-horsed their way into something called a “dictionary,” which the

author was then allowed to revisit, rewrite, and build upon for the next

40 years.

The days of that kind of publishing miracle—not to mention the days

of bound reference books that people pull off shelves to consult and

periodically replace with updated editions—would seem to be numbered.

Thomson implies in the book’s introduction that this sixth edition may

be the book’s last. (Then again, he suggested something very similar in

the foreword to the last edition four years ago.) This new introduction

begins with a melancholy salute to the dictionary’s original editor, the

late Tom Rosenthal,

who stood up for the project when it began to veer far afield of the

tidy reference volume originally conceived by the publisher. Describing

Rosenthal’s initial reaction to the manuscript, Thomson writes, “[I]n

his most splendid and grave way he agreed … that it was growing into

some kind of monster, the fate of which he could not predict, but he

felt it was arresting and passionate, and he said I should proceed.” We

should all have such an editor once in our lives. Readers have Rosenthal

to thank for the existence and longevity of this strange, passionate

monster of a book, which, love it or hate it, belongs on the shelf of

every serious cinephile.

After going through the sixth edition compiling quotes for this essay

(and falling down the usual 20-minute rabbit hole with each entry), I

had such a pile of unused gems that I want to append a quick list of

short passages, to give a sense of the range of Thomson’s voice and

opinions on cinematic personalities past and present.

On Lena Dunham:

“A few things can be established: Tiny Furniture, no matter that it cost $65,000 and employed her own family members … was a stylish comedy poised neatly between mumblecore and Lubitsch. She is a very smart scriptwriter. She has as good an eye as her ear. And she has no hesitation in showing off her body the way John Ford displayed Monument Valley.”

“A few things can be established: Tiny Furniture, no matter that it cost $65,000 and employed her own family members … was a stylish comedy poised neatly between mumblecore and Lubitsch. She is a very smart scriptwriter. She has as good an eye as her ear. And she has no hesitation in showing off her body the way John Ford displayed Monument Valley.”

On Joaquin Phoenix:

“In several ways, he provokes comparisons with Brando in his evident dismay over acting. But he has never delivered the precision or the beauty that belonged to Brando. I have the feeling that he may end up naked and silent in a Lars von Trier picture, hoping he’s not there, with his mouth twisted like the Cheshire Cat’s grin. Or will he be our greatest actor?”

“In several ways, he provokes comparisons with Brando in his evident dismay over acting. But he has never delivered the precision or the beauty that belonged to Brando. I have the feeling that he may end up naked and silent in a Lars von Trier picture, hoping he’s not there, with his mouth twisted like the Cheshire Cat’s grin. Or will he be our greatest actor?”

On James Franco:

“… [I]f anyone can get films made of As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury in this world and time, you have to hand it to that guy—it doesn’t matter if the films are any good, he is an operator. … He is immensely sympathetic and entirely implausible; he has over ninety credits already—and I promised only a few hundred words. He is Gatsby—and better him than Leonardo DiCaprio!”

On Howard Hawks:

“Like Monet forever painting lilies or Bonnard always re-creating his wife in her bath, Hawks made only one artwork. It is the principle of that movie that men are more expressive rolling a cigarette than saving the world. ... The dazzling battles of word, innuendo, glance and gesture—between Grant and Hepburn, Grand and Jean Arthur, Grant and Rosalind Russell, John Barrymore and Carole Lombard …—are Utopian procrastinations to avert the paraphernalia of released love that can only expend itself. In other words, Hawks is at his best in moments when nothing happens beyond people arguing about what might happen or has happened.”

“… [I]f anyone can get films made of As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury in this world and time, you have to hand it to that guy—it doesn’t matter if the films are any good, he is an operator. … He is immensely sympathetic and entirely implausible; he has over ninety credits already—and I promised only a few hundred words. He is Gatsby—and better him than Leonardo DiCaprio!”

On Howard Hawks:

“Like Monet forever painting lilies or Bonnard always re-creating his wife in her bath, Hawks made only one artwork. It is the principle of that movie that men are more expressive rolling a cigarette than saving the world. ... The dazzling battles of word, innuendo, glance and gesture—between Grant and Hepburn, Grand and Jean Arthur, Grant and Rosalind Russell, John Barrymore and Carole Lombard …—are Utopian procrastinations to avert the paraphernalia of released love that can only expend itself. In other words, Hawks is at his best in moments when nothing happens beyond people arguing about what might happen or has happened.”

On John Cazale, who played the doomed Fredo Corleone in The Godfather and died of bone cancer in 1978:

“I don’t have anything else to say except that it is the lives and

work of people like John Cazale that make filmgoing worthwhile. In

heaven, I hope, there will be no stars, just supporting actors. And one

of the great strengths of American film is such people. But it is a

weakness, too, in that the code continues to insist there are more

important people. There are not. So watch Cazale in The Godfather: Part II addicted to daiquiris and the women he can’t keep in order—he is the only hope in that terrible family.”

By Dana Stevens

With thanks to Slate

See also:

How Sergio Leone’s Westerns Changed Cinema

Top 10 Movie Twists of All Time

Oscar Winners 2016: The Full List

See also:

How Sergio Leone’s Westerns Changed Cinema

Top 10 Movie Twists of All Time

Oscar Winners 2016: The Full List

Biopics Now Focus On Key Moments Rather Than A Whole Life

The Best Movies Of 2014

Some Biopic Actors And Their Real-Life Counterparts

23 James Bond Themes And How They Charted

10 Historical Movies That Mostly Get It Right

Long-Lost Peter Sellers Films Found In Rubbish Skip

Are These The Top 10 Comedy Actors of All Time?

The Best Movies Of 2014

Some Biopic Actors And Their Real-Life Counterparts

23 James Bond Themes And How They Charted

10 Historical Movies That Mostly Get It Right

Long-Lost Peter Sellers Films Found In Rubbish Skip

Are These The Top 10 Comedy Actors of All Time?