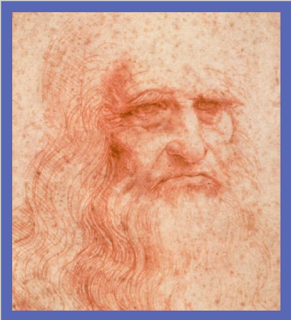

Everybody knows about Leonardo da Vinci, and much of what they know is wrong.

The story of the Tuscan notary’s bastard child who was wafted up to the summit of the Renaissance on the thermals of his own genius is so familiar as to be almost invisible, like the nastiness hidden in the words of nursery rhymes. Leonardo is part of the furniture, the world’s mad uncle — Einstein, Van Gogh and Heath Robinson rolled into one global super-meme.

Among the millions who clog up the Louvre each year for a fleeting half-glimpse of the Mona Lisa, how many know that the man who painted it also built the first tank, the first helicopter and the first scuba apparatus a good four centuries before their time? Probably a solid majority. How many of them realise that this “fact” is a tissue of fascist revisionism put together on the direct orders of Mussolini? Maybe only a handful.

Next month an exhibition at London’s Science Museum, Leonardo da Vinci: The Mechanics of Genius, will wrestle with the hardest questions of all about Leonardo: why is the world so incurably fascinated with a man who had almost no effect on the course of history? Did the original nutty inventor really invent anything at all?

These might seem like odd things to ask about a master engineer. After all, the centrepiece of the show will be 39 not-quite-life-sized models based on the sketches in Leonardo’s notebooks. All the greatest hits are there: the pyramid-shaped parachute; the bat-winged flying boat; a floating siege weapon for crossing moats and clobbering the walls inside. There is even a cube on wheels, designed to be driven by the wind.

Yet none of these contraptions was built in Leonardo’s day. Many of the more plausible devices are mere copies of the machines he saw springing up in the busy technological revolution unfolding across Italy. A monumental crane for raising columns was borrowed wholesale from Filippo Brunelleschi, the architect who raised the dome over Florence Cathedral.

Claudio Giorgione, curator of the Science Museum show, thinks Leonardo was absolutely right on that score. “He didn’t publish his work,” Giorgione says. “Most of the drawings we have in the notebooks are a sort of very, very large diary. In the second half of his life he tried to prepare a treatise on mechanics and hydraulic engineering, but he didn’t have the time to share his findings.”

You might reasonably ask why the Science Museum, of all places, would lavish all this effort on a man whose technical achievements did not even begin to come to light until 300 years after his death. The answer is that all the brilliance dissipated in those notebooks has an enormous amount to teach us today.

Leonardo lived in an age when art and science were not differentiated into separate disciplines as they are now. His paintings and all of the fantastical machines that mushroomed out of his observations were one and the same. This was a mind that could spot the mechanism powering a timepiece and design it into a flying crossbow, or spend hours minutely cataloguing the soft fall of light through a window only to develop it into the smouldering sfumato of The Last Supper.

He was a remarkable draftsman and mathematician, but what he had in abundance was a sense of the world as a vast piece of clockwork whose parts were infinitely interchangeable. We are only just coming to realise the value of this view today. A large section of the Science Museum’s show will be dedicated to biomimicry, the modern art of stealing the tricks nature has evolved over millions of years.

Just as Leonardo obsessed over the way air flows around a bird’s wings as it glides and dreamt of human flight, so scientists are assembling swarms of tiny drones that imitate the flight of bees, or copying the nanostructures of spider-silk to spin materials that are harder than steel and lighter than cotton.

More endearingly, Leonardo’s special brand of playfulness could be rollicking good fun. In 1490, while he was at the court of the Sforzas in Milan, he was asked to design the set and costumes for a performance of Bernardo Bellincioni’s masque Il Paradiso at the young duke’s wedding to Isabella of Aragon. On the stroke of midnight, the curtains were drawn to reveal Leonardo’s paradise, an enormous half-egg slathered in gilt and lit up with a night sky’s worth of candles. The seven known planets were arranged in a perfect facsimile of the solar system. Giorgione, who has rebuilt the set into a miniature theatre for visitors to toy with, calls it the world’s first planetarium.

There was also a kind of mercenary helplessness to Leonardo. Not long after the French took Milan in 1499, he found himself in charge of the special effects for Poliziano’s operetta Orfeo. A great sweep of rugged mountains opened up to disgorge Pluto, the king of the Underworld, prowling in his cavern. But months later he was back to dreaming up guns and siege engines for his new overlords with the same childish relish. The exhibition features a model of his absurd, wheeled wigwam of cannon based on drawings that were cut away to reveal the exquisite mechanics of death inside.

“This is a paradox,” Giorgione says. “He writes at more than one point in his life that he didn’t like war and he considered it a crazy thing to pursue, but at the same time he works so much on military weaponry. Because he was a very pragmatic man, he knew that this was one of the keys to enter the court, to get close to the dukes and get their attention and money to carry on with all his other studies.”

Leonardo owes a large debt to a much more recent tyrant.

The myth of Leonardo the inventor only really took off in Milan on the brink of World War II. Mussolini wanted a hero to demonstrate Italy’s congenital mastery over science, technology and the arts. He found Leonardo. The dictator commissioned scholars to design the first set of comprehensive models based on the sketches in Leonardo’s long-neglected notebooks. Built on a monumental scale in blood red and inky black, the flying machines and wild engines of war were exhibited in 1939 alongside other triumphs of Italian engineering such as the country’s first television shows. The message was not a subtle one. The aim was, as the show’s program noted in the clanking prose of autocracy, “to demonstrate the continuity of the creative genius of the race and the great possibilities opening up to those within the climate of fascist will”.

Astonishingly, it stuck. Mussolini’s models may have been lost on a ship somewhere in the north Pacific, but their ghosts live on.

Yet these machines were never meant to be. One of the inspirations for the new show was Giuseppe Pagano, a leading Fascist party architect who worked on Mussolini’s Leonardo exhibition but later turned dissident and ended up dying in an Austrian concentration camp in 1945. Even at the time, Pagano saw a striking beauty in the impracticality of the drawings. “Rather than machines to be patented,” he wrote in his notes, “these became rational devices, mechanical experiments of sublime value.”

What Pagano realised, and what emerges strongly from the Science Museum show, is that Leonardo was really the opposite of an inventor. He was a man whose mind raced from the stoop of a falcon or the churning of a water wheel to the higher ground of abstract reasoning. Behind all of the museum’s interactive sketchbooks and haunting models is this search for a “universal knowledge” in which everything that moves is set out in its place like the spheres in an orrery.

Like Socrates in Plato’s Republic, Leonardo saw the physical world with all its messy interactions as a series of problems that led upwards through mathematics and logic to a single, divine truth that resides as much in the heart as in the head. And this is the greatest legacy that he has left for us today: a vision of a world entirely composed of shades of light and wheels forever turning.

By Oliver Moody

With many thanks to The Australian

Leonardo Da Vinci's: The Leicester Codex sale price.

Great Minds: Filippo Brunelleschi

Great Minds: Leonardo da Vinci

The Isleworth Mona Lisa: A Second Leonardo Masterpiece?

Vincenzo Peruggia: The Man Who Stole The Mona Lisa And Made Her more Famous Than Ever

The World’s Priceless Treasures

What Was the Enlightenment?

Quantum Enigma Machines Are Becoming A Reality

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: The Philosopher Who Helped Create the Information Age