To design a map of the world is no easy task. Because maps represent the spherical Earth in 2D form, they cannot help but be distorted, which is why Greenland and Antarctica usually look far more gigantic than they really are, while Africa appears vastly smaller than its true size. The AuthaGraph World Map tries to correct these issues, showing the world closer to how it actually is in all its spherical glory.

Created by Hajime Narukawa at Keio University's Graduate

School of Media and Governance in Tokyo, the design just won the grand

prize from Japan’s Good Design Award as Spoon & Tamago reports. It beat out over 1000 entries in a variety of categories.

Unlike the Mercator projection, the 1569 mapping technique

that you'd probably recognize from the world maps you saw in school,

the continents on the AuthaGraph aren’t lined up straight across—they’re

angled in a way that provides a more accurate representation of the

distances between them. “AuthaGraph faithfully represents all oceans

[and] continents, including the neglected Antarctica,” according to the

Good Design Awards, and provides “an advanced precise perspective of our

planet.” No longer does Africa look the same size as North America, or

Antarctica look like one of the biggest continents (it’s smaller than

everything but Europe and Australia).

The map—which is used in Japanese textbooks—can be fit into different shapes without losing its accuracy, and AuthaGraph sells

paper assembly kits where you can fold it from a sphere to a cone to a

flat map, mimicking the way the projection itself is made.

By Shaunacy Ferro

With many thanks to Mental Floss

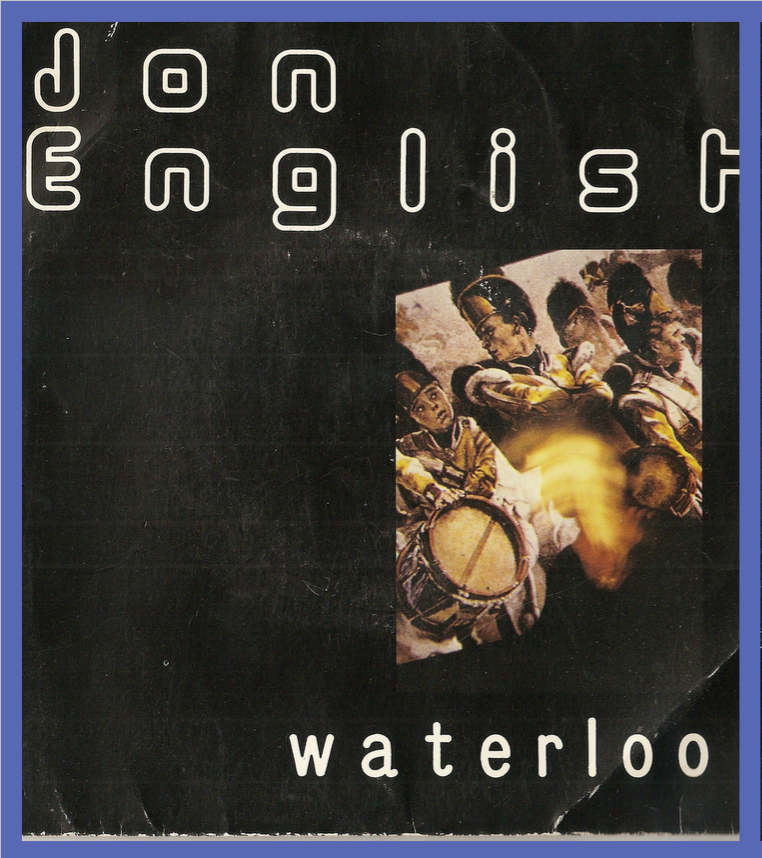

Napoleon Met His Waterloo Because He Used The Wrong Map!